Aston Villa v xG: Villa Twitter's war on nerdy numbers explained

Unai Emery's Villa are flying high in the Premier League and the expected goals row is just adding to the fun

Unsustainable FC. That’s what they say, anyway. Early in Aston Villa’s positive run of form they scored nine goals from outside the penalty area one after the other, winning matches without making many clear chances.

Villa started the Premier League season in awful shape, drawing three and losing two of their first five matches. We can speculate about the reasons for it but we know it wasn’t a fluke. Villa were terrible.

Those performances were represented most obviously by a dearth of chances and shots. Villa supporters know that because they watched the games. They saw it. They felt it. They didn’t need statistics to tell them.

Nevertheless, that is what the statistics would have told them.

Villa’s expected goals (xG), chance creation, shots on target – you name it, they were trundling along with the lowest numbers in the Premier League or thereabouts.

They weren’t exactly aligned – they seldom are – but those numbers broadly agreed with the eye test. Villa lacked creative cut-through and weren’t generating good chances at a high enough volume.

Why are Villa supporters kicking off about xG?

If you’ve spent any time at all on social media or with Villa supporters since the team started putting points on the board at a league-leading rate, you’ll have seen the brewing battle between some fans and a section of the football data community.

At its root is the difference between Villa’s performance on the pitch and their xG. By scoring regularly from outside the penalty area at a click that was essentially superhuman, Villa outstripped the quality and volume of their chances with the goals they were scoring.

Up the table they went. Their xG didn’t go with them (though it has gradually increased), which has birthed this rift between factions.

Villa got their shit together by scoring a load of incredible goals rather than by substantially improving their generation of quality chances. It’s been hugely exciting and developing an alternative method of beating a low block is perfectly cromulent way to win matches.

The disparity leaves a vacuum into which narrative must leak. Villa were defying the data and the way that information is presented, used, interpreted and understood caused some lively bickering.

Villa’s performance levels raised the question of sustainability, and fair enough. It’s unlikely that a team is going to score all its goals from low-quality chances and Villa themselves have shown that in the last few matches.

It was probable (not inevitable) that Villa would go one of two ways: start to create more and better chances or stop scoring and drop down the table.

Players like Morgan Rogers blasting in belters from outside the penalty area is an advantage for Villa. Underlying statistics don’t contradict that. If anything, they back it up and highlight the benefit. Whether it’s sustainable or not is up to you.

xG still has a presentation problem

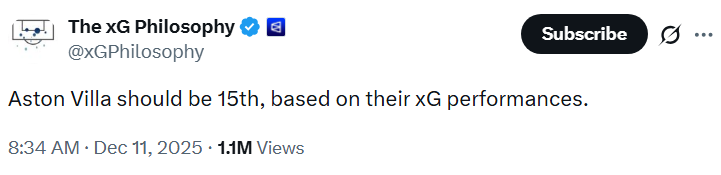

One online exchange in particular caught my attention. You’ve probably seen it too.

It started with a Twitter account called The xG Philosophy, which has been around forever and specialises in punting out xG data.

The tweet in question got a few backs up among the Villa support.

It’s a pretty typical example of xG being misrepresented and the problem is the word should.

It’s there as ragebait – my guess is the person behind the account knows what they’re doing in that regard – or as a loose piece of language that does a disservice to the numbers it purports to be presenting.

You know where Aston Villa should have been on December 11th 2025?

Third.

But they were 15th in a ranking of every Premier League team by their xG. You can find that interesting and illustrative or not, but xG is one of hundreds of statistical measurements used in combination by managers, coaches, scouts and analysts at every professional football club in the world.

What those analysts are not doing is taking the xG total for the season so far and suggesting that a team should be somewhere they’re not.

I don’t know why xG was adopted as a simple and noteworthy statistic by the media and used in a match context but it’s been showing up as some sort of alternative score for ages now, from Match of the Day down.

Here’s an example from Sunday’s win against West Ham United. It was a 3-2 away win, by the way.

Now, I like and use xG. I think it’s an essential starting point for behind-the-scenes analysis at our clubs and is the basis upon which patterns can be interpreted over time.

With associated data, it can help teams understand strengths, weaknesses and potential problems coming down the pipe.

But 1.21 v 0.68 in one match? Fucking nonsense. Pointless. Misleading. It’s presented in that way to be a talking point but all we can take from it is that West Ham over-performed xG by 0.79 goals and Villa over-performed xG by 2.32 goals in that one game.

So what? It doesn’t say Villa should have lost by half a goal any more than they should be 15th. It’s useful long-term data wrapped up in immediate guff and it barely scratches the surface in terms of misrepresenting xG for public consumption.

So, what is the point of xG then?

But that doesn’t mean xG in itself is ‘horseshit’ or ‘meaningless’ or any of the other labels I’ve seen applied to it by Villa supporters in the last couple of days. I can guarantee it’s tracked within the club, for starters.

Let’s go back to the beginning. Here’s Opta’s explanation:

“Expected goals (or xG) measures the quality of a chance by calculating the likelihood that it will be scored by using information on similar shots in the past. We use nearly one million shots from Opta’s historical database to measure xG on a scale between zero and one, where zero represents a chance that is impossible to score, and one represents a chance that a player would be expected to score every single time.”

Emphasis mine.

Opta explains that these hundreds of thousands of shots have been analysed based on ‘over 20 variables’ that include: distance and angle to the goal, the position of the goalkeeper and other players, pressure from defenders, and the type of shot taken.

Based on all that, Rogers’ second goal against West Ham had an xG of 0.02 according to some sources, which means that a player can be expected to score with that type of shot, from that position, in that situation, one time in 50 attempts. Not Rogers specifically, but any player that would belong in that massive dataset.

Do you, like me, think Rogers would score at a much higher probability than one in 50? Great! That’s why a neutral average can be instructive. Rogers is better at that shot than ‘expected’ and we have a statistical illustration to support that.

Upgrade now for wraparound match coverage and other features for just £4 per month.

xG isn’t there to describe one shot. Repeat that calculation for every shot over the course of a season and it’s easy enough to understand how over-performance or under-performance versus xG is one of many handy things for club analysts to know about players, about team performance, about playing style, about chance quality and frequency, about tactics.

If Emery sees that Villa’s xG is the lowest in the Premier League (it’s also worth noting that I’ve avoided words like ‘best’ and ‘worst’, just as I’ve avoided ‘should) he might look to address it any number of ways.

Villa might start working on shooting from distance, for example, or look to generate more chances of a higher quality from set pieces. They might seek to create a higher number of high-quality chances or maximise their real-world output from lower-quality chances.

xG is football statistical carbon, the essential building block of data that tells clubs what’s good, what’s bad and how to fix it.

It’s not about Villa being lucky or fluking their way up the table, but about Villa’s analysts plugging it into a bunch of other stuff to strategise longer-term and to assess things like the performance of Ollie Watkins (how’s he doing against the xG of the shots he’s taking, for example, and what does that xG tell us about his service) or Emiliano Martínez (how is he performing against his PSxG, or post-shot xG, which is the likelihood of a goal measured after the shot is taken to determine how many goals above or below expected a goalkeeper concedes).

That doesn’t seem pointless to me and the fact that this information is all player-neutral is what makes it potent in terms of performance measurement.

Yes, it’s obvious that the data will show that Rogers is better than average at taking chances, but over time it’ll be used to identify deviations in his performance with those chances. It’s the first step towards solving a problem or maximising a positive anomaly.

Really, though, all this isn’t for bite-sized consumption on television chyrons or over-zealous single-purpose social media accounts.

xG in its simplest sense isn’t there to tell us anything about what should be happening in a match or a league table, nor is it to be taken as a straightforward predictive metric.

Football is too damned complicated for that but Villa supporters shouldn’t throw the xBaby out with the actual bathwater because they’ve been taken in by lazy presentation.